Srry Stealer Analysis

Summary

-

This malware was categorized as “SrryStealer” found on MalwareBazaar

-

The malware originated from "mythictherapy[.]org", and the sample reached out to “linnisgood[.]site”, likely a C2. Both domains no longer resolve, suggesting this sample is dead.

-

The sample is a NSIS installer (originally named MythicTInstaller.exe), which installs and runs an electron application called MythicT24Setup.exe.

-

The Electron application was observed reaching out to the C2 server, but was not observed accessing any files as we would expect a stealer to.

-

Techniques used:

-

Static analysis: Detect It Easy was used to identify files. 7zip was used to extract the installer files as well as the Electron JS code from app.asar. Code analysis was performed on the NSIS install script as well as the JS code. VirusTotal was used to observe dropped files and other behavioural information.

-

Dynamic analysis: ProcMon, ProcessHacker, FakeNet-NG, and PowerShell logging were used within a FlareVM virtual machine to observe the sample’s behaviour. The only suspicious behaviour observed was the reaching out to the C2 server, observed in both ProcMon and FakeNet-NG.

-

Debugging: Visual Studio Code was used to analyze the heavily obfuscated JS code run by the Electron application.

-

Memory forensics: The memory of the running process was dumped to search for suspicious strings, but nothing was found.

-

-

Further work:

-

While I was able to determine how the beginning of the JS code worked, it did not appear like it would ever resolve. Further analysis would need to be performed to determine if there was a way around it or if the JS code was a red-herring.

-

Other SrryStealer samples could be analyzed to see if they are still alive, which would allow further dynamic analysis and a better idea of this malware family’s behaviour.

-

Background

This is an analysis of a malware sample with the tag “SrryStealer” found on MalwareBazaar. The sample’s original name was MythicTInstaller.exe, which appears to be related to the domain “mythictherapy[.]org” which was also a tag. The sample was first seen on 2024-03-26 15:53:26 UTC, and the first submission of the sample to VirusTotal was 2024-03-26 15:33:59 UTC.

From a cursory Google search, there does not appear to be any in-depth analyses available for SrryStealer yet, outside of a high-level notice given by Broadcom. The goal for this analysis will be to identify IOCs for this particular sample as well as to understand the infection chain associated with this SrryStealer sample.

IOCs

| Type | Indicator | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Domain | mythictherapy[.]org | The site apparently associated with the sample |

| SHA256 | 0147881f61d051b5918be81ce9fcab18e9b629be393b8065e50cc286d53f8927 | The executable sample |

| SHA256 | 7649540d9d072df546b6b436b6a9784e58fde827ddc268465d800c2fae753724 | Dropped MythicT24Setup.exe Electron Executable |

| SHA256 | 935c086fd04d537e5fe8ea9e3d99599f14b6957fa9f991009f76d1e2c17235d0 | Dropped Uninstall MythicT24Setup.exe file |

| Domain | linnisgood[.]site | C2 server the application reaches out to |

Sample Analysis

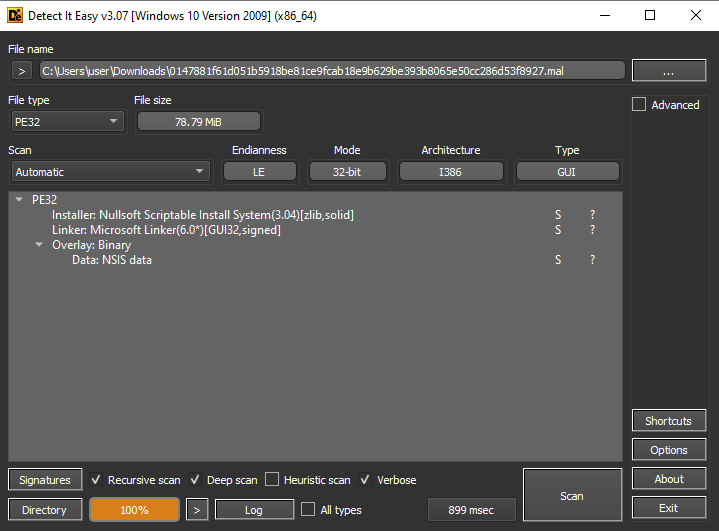

Executable

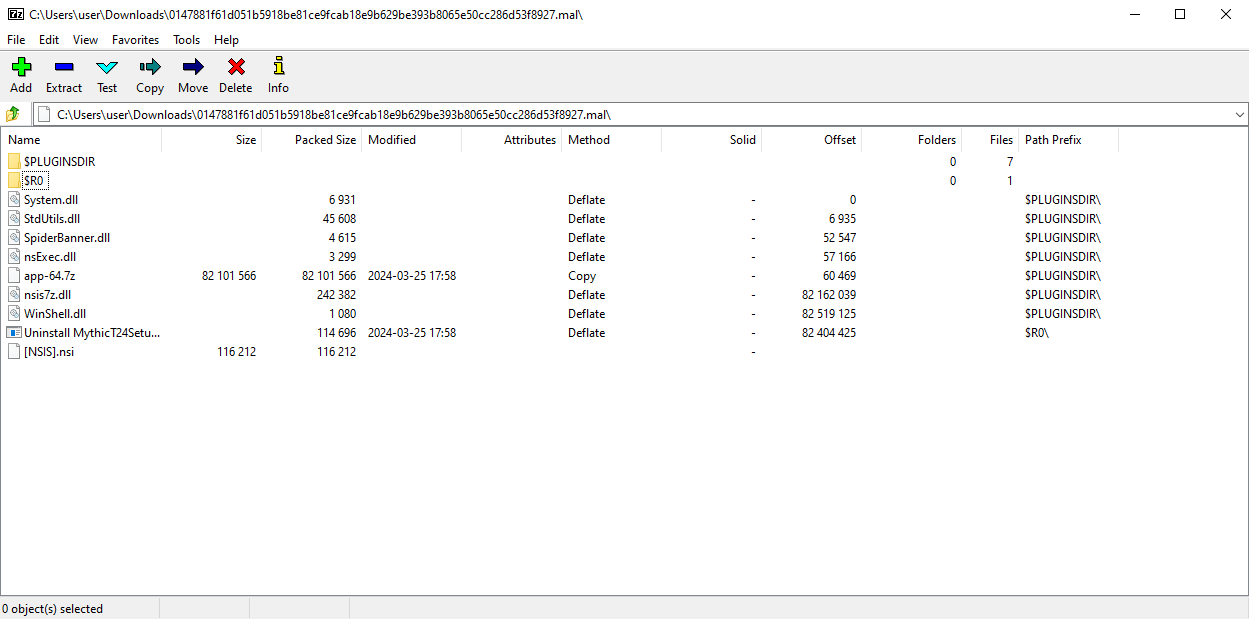

The sample is a Portable executable file, 32 bit. Detect It Easy detects the sample as being created with Nullsoft Scriptable Install System (NSIS), which is a script-based system for creating Windows installers. From Didier Stevens' quick analysis of a NSIS-based malware, I discovered that we can open up this NSIS install file with 7zip, allowing us to extract the install files as well as the NSIS script. The results are shown in a flat view below:

The most interesting files appear to be:

-

app-64.7z: could this hold the installed application?

-

[NSIS].nsi: The NSIS install script

-

Uninstall MythicT24Setup.exe: This again appears to be a reference to the mythictherapy[.]org domain. Could the user think they are downloading a “mythic” application from this website?

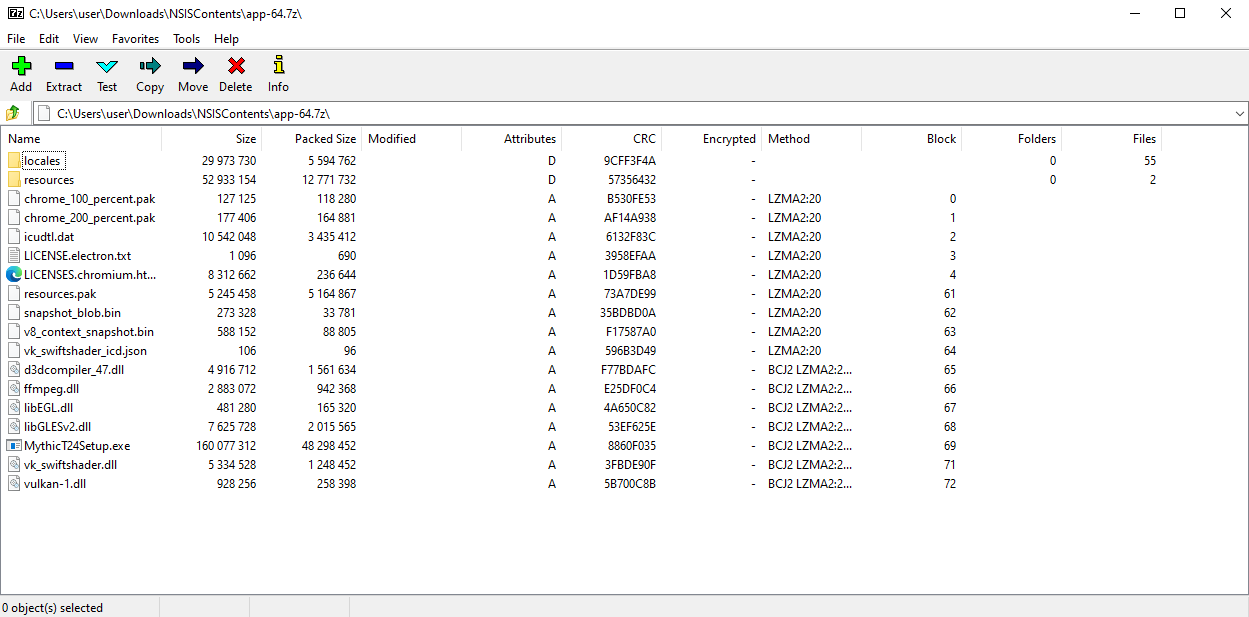

app-64.7z

This is just a 7zip file, that contains the files related to the installation of an executable called “MythicT24Setup.exe”:

Based only on this 7zip output, this would appear to be an electron application.

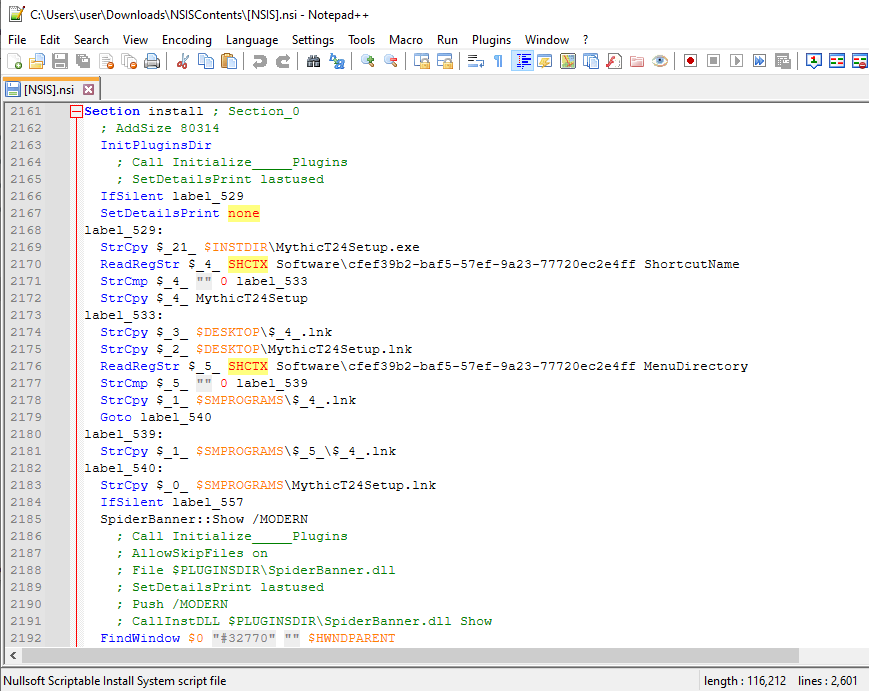

NSIS Install Script

Taking a hint again from the Didier Stevens article, I jumped straight to the section marked Section_0:

There begins with apparent checks to see if MythicT24Setup.exe is running, under some conditions it will try to kill them.

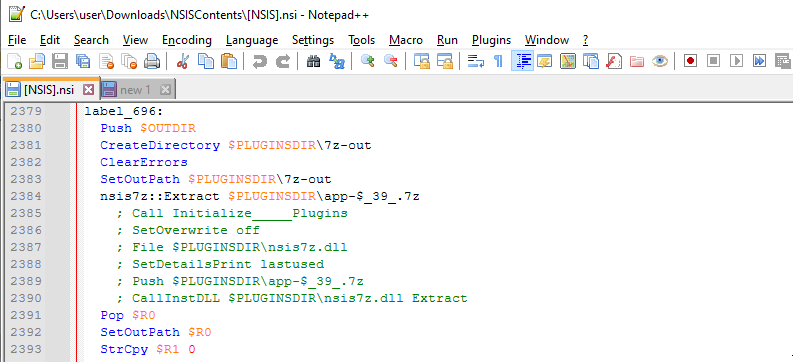

Later in the section, we find the part where the app 7zip is extracted.

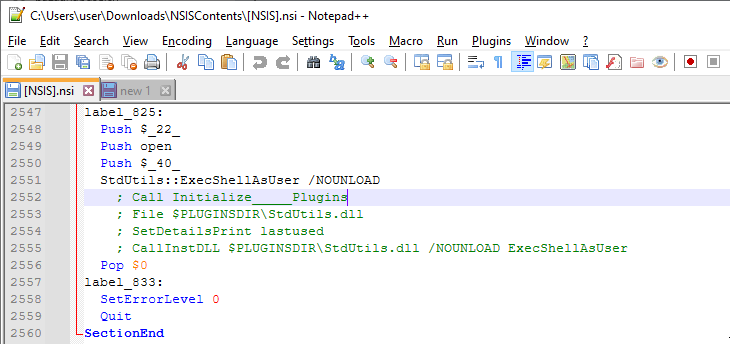

At the end of the section, I found the following code snippet:

ExecShellAsUser is being called, following the pushing of a couple values. The first variable being pushed, `$_22_` is earlier set to MythicT24Setup.exe via ``StrCpy $_22_ $INSTDIR\MythicT24Setup.exe``. This suggests to me that the last step of this install section is to execute that file.

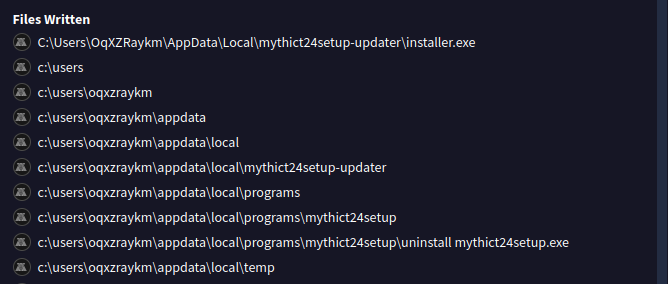

In VirusTotal, we can see that these files are being written to AppData:

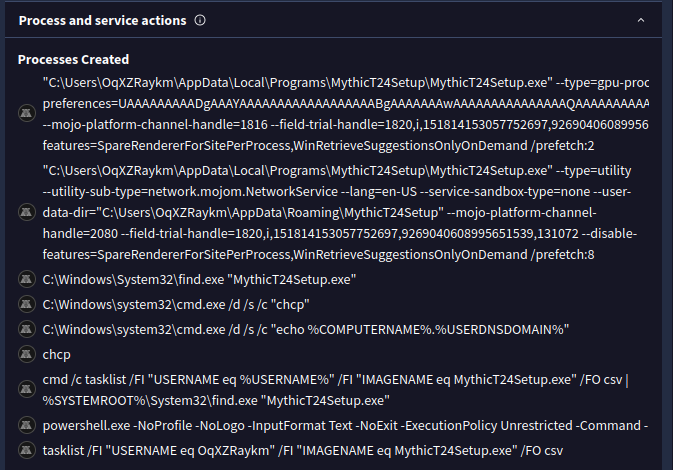

VirusTotal also confirms that we can see that written MythicT24Setup exe being created as a new process:

Analyzing the Electron Application

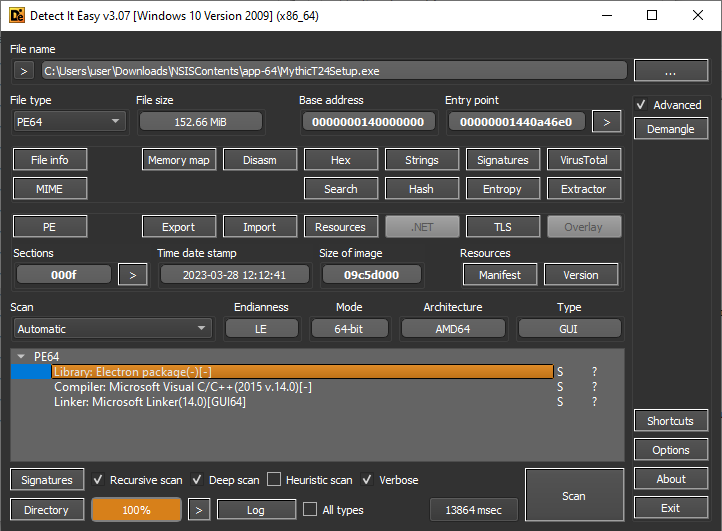

Now that we know that the installer is dropping the electron application and running it, we’d like to analyze the application. First we can use Detect It Easy to confirm that the application is electron-based:

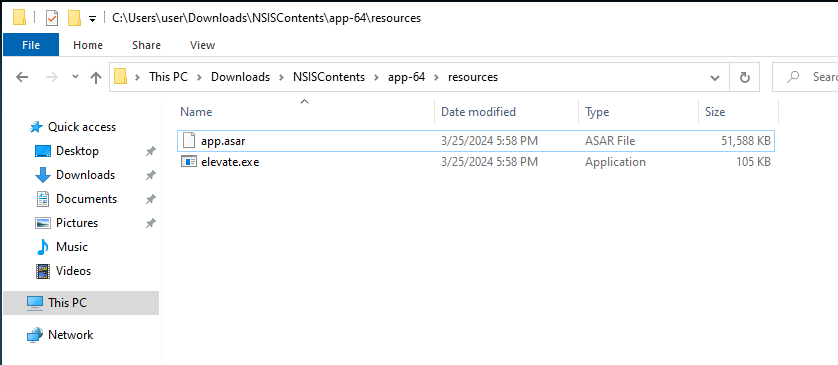

Then, I looked up techniques for analyzing Electron-based malware, and discovered this video by Malware Analysis for Hedgehogs. The code for electron applications, rather than being stored in the large executable, is actually stored in the “resources\app.asar” file within the install directory.

To extract the data from this file, we can use an asar 7zip extension. After installing that tool, we can extract the file with 7zip:

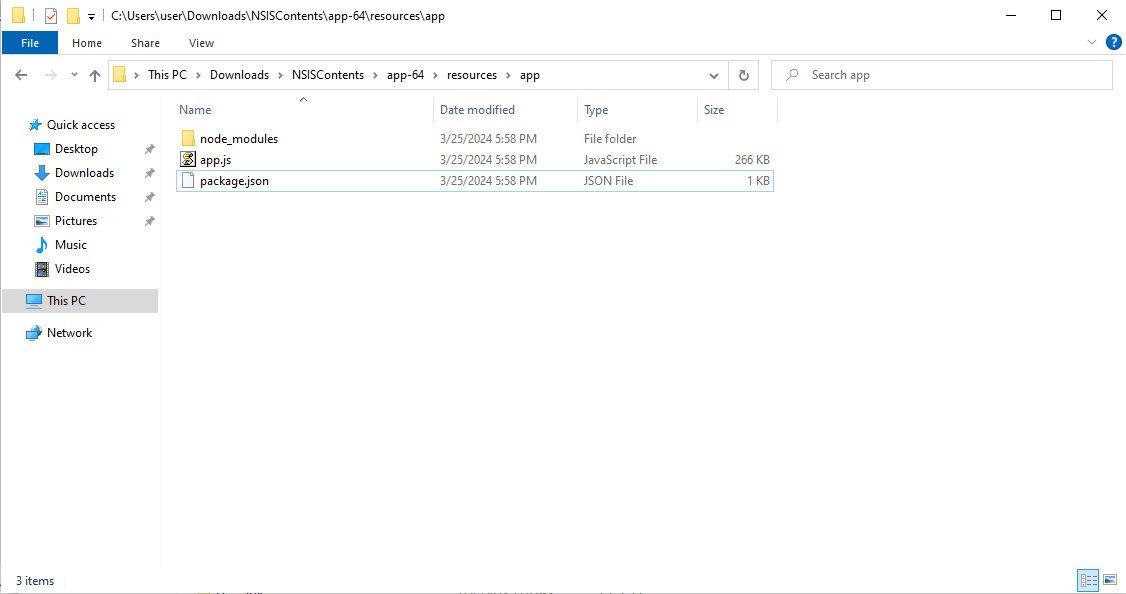

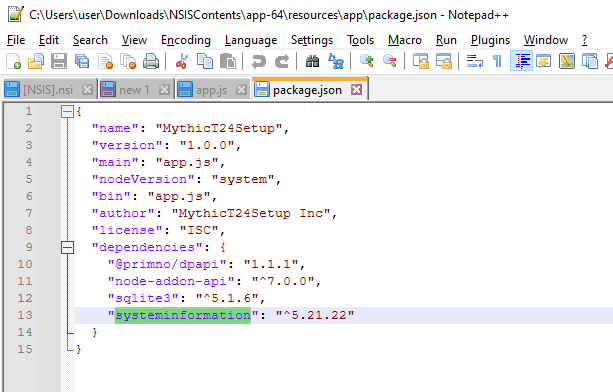

package.json

The most notable thing here is the dependency on Primno’s DPAPI extension, which allows the application to unprotect data on Windows. This is expected functionality from a stealer, as protect data is commonly used to encrypt sensitive data stored by browsers.

app.js

This is a fairly large obfuscated file, which is 1680 lines after running through de4js. Given the complexity of the file, I decided to start performing dynamic analysis at this point.

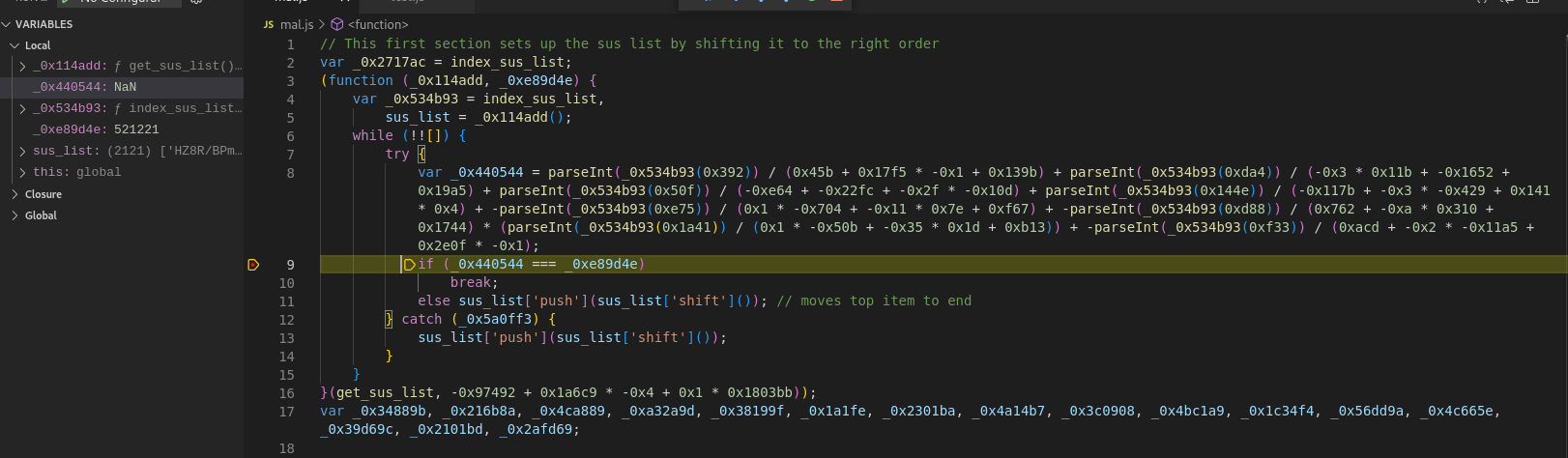

The first thing I noticed, running the sample, was that the CPU usage spiked dramatically. This seems to be because the code is using the strategy of creating a list with all of the codes and then indexing them, and then running a loop over which pushes them around until they are in the right order. The reason why I wasn’t seeing anything in Procmon is probably because this process just wasn’t completing.

Moving over to Remnux, I tried dynamically analyzing the JS code on its own:

The first block is where the code gets stuck in the debugger, for hours, without completing. The condition for exiting the loop is when the computed sum _0x440544 equals 521221. The computed sum is based on a complicated expression drawing values from a list of strings which appear to be obfuscated. At the end of each loop iteration, if unsuccessful, the top element of this list is pushed to the back. Eventually, I would expect this to result in the correct ordering.

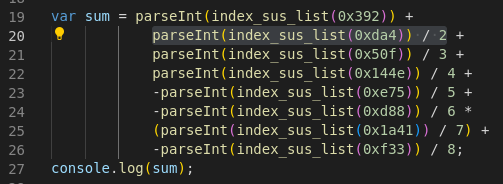

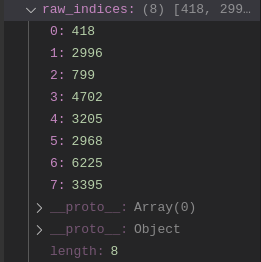

However, notably, after untangling the sum and calculating the actual indices, I found the following:

Many of the indices are far out of bounds of the list, which has 2121 elements. Since the modifications made to the list do not affect its size, we actually would never expect the sum to be anything but NaN. I am at this point not sure how to continue: unless I am missing something, I wouldn’t expect the rest of the code in the file to run.

Dynamic Analysis

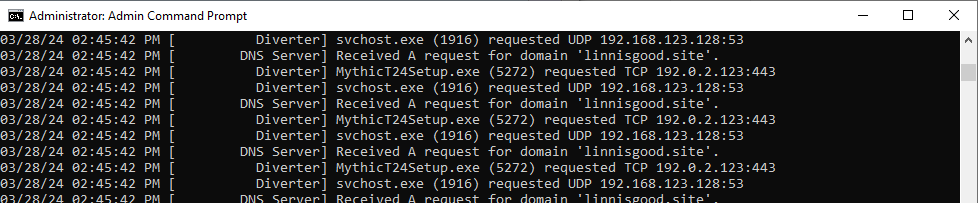

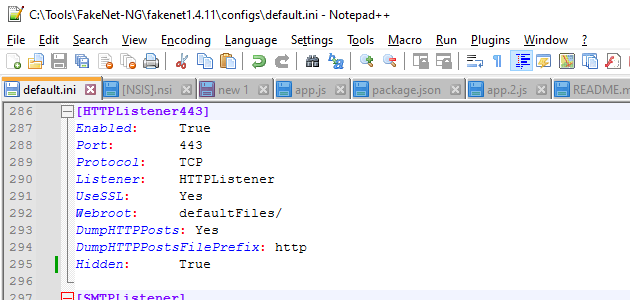

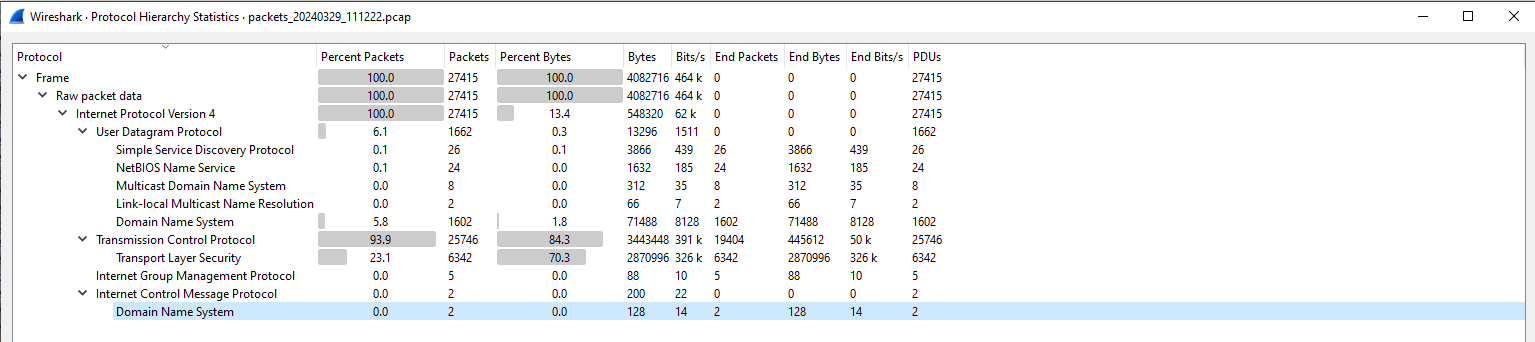

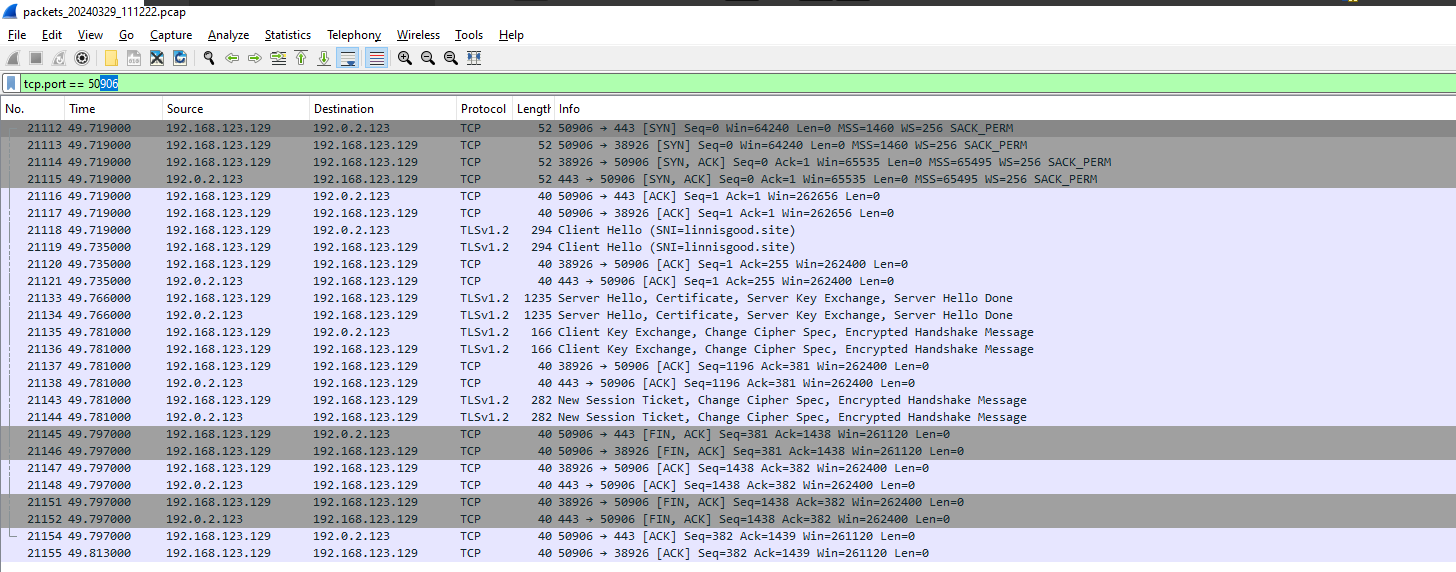

First, I launched the MythicT24Setup.exe electron application while FakeNetNG was running.

This revealed many DNS requests for the domain “linnisgood[.]site”, which has detections on VirusTotal:

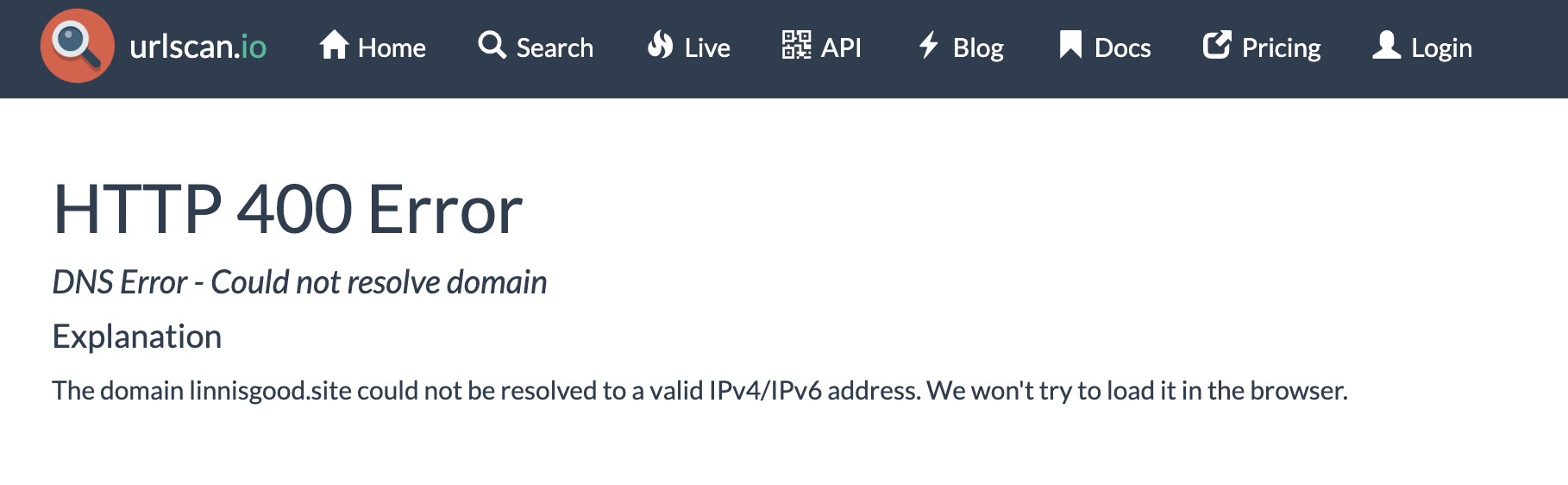

However, this domain no longer appears to be active:

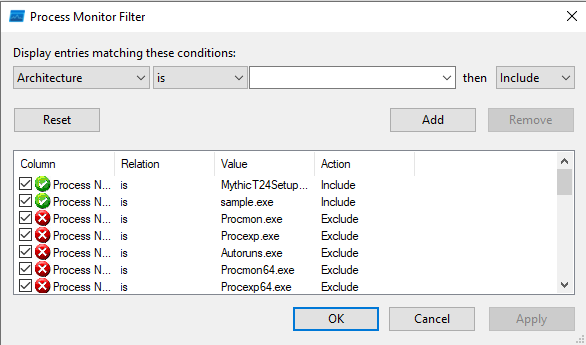

However, for the following filters on procmon, nothing suspicious is noticed:

I don’t see any of the behaviour that I would expect to see from a stealer, like the reading of Chrome data files.

Strings

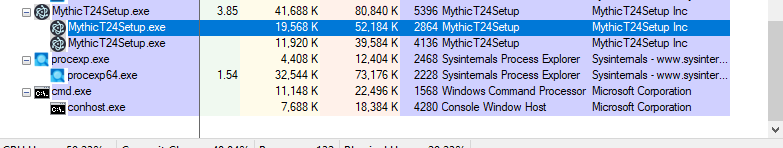

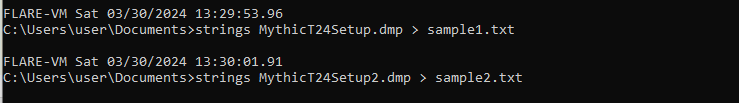

To see if I could find suspicious strings, I used Process Hacker to get dumps for two of the MythicT24Setup processes.

I found references to the C2 domain within the first set of strings,

which confirms that it is this process that is reaching out.

However, I don’t find any reference to files or file paths that we would expect from a stealer. If the C2 was still alive, the sample may have received those from it.

Further Dynamic Analysis

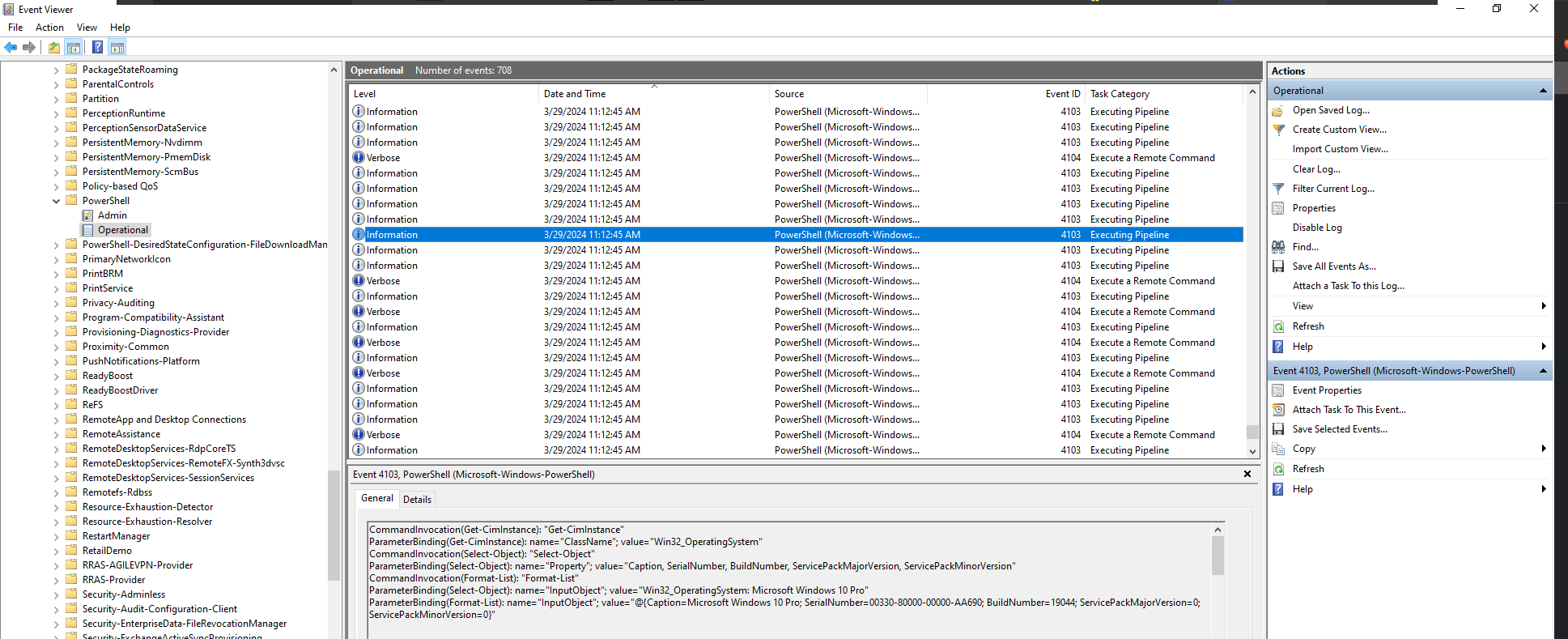

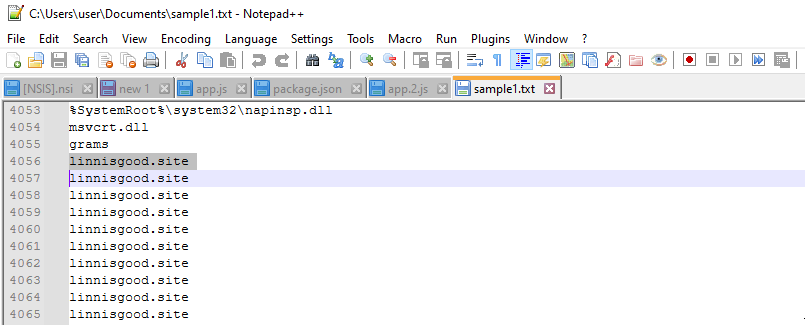

Going to try to use Powershell logging, as I see powershell being run in Procmon

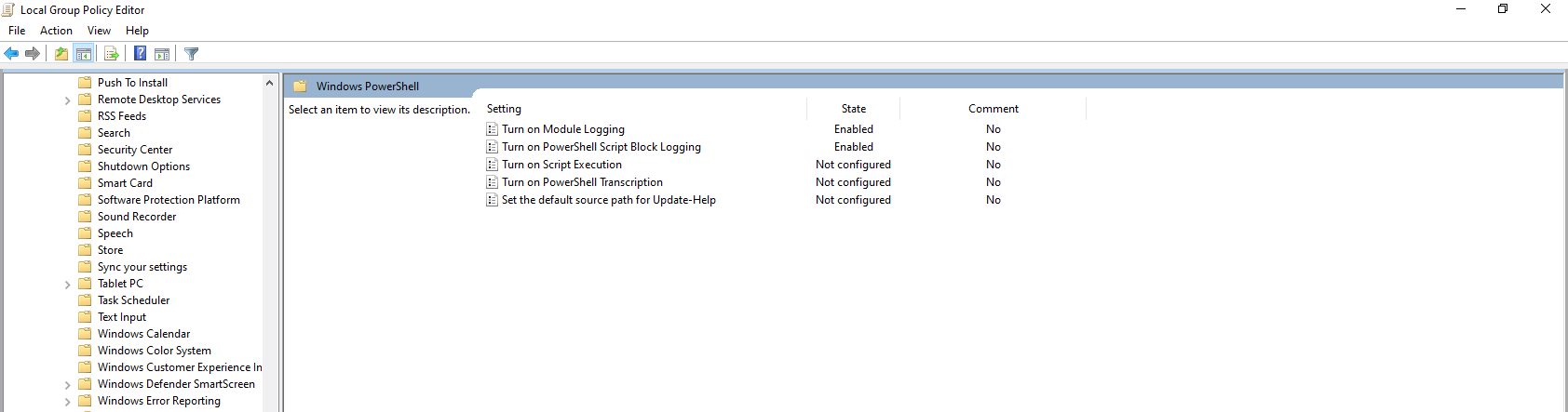

I’m also going to try to turn on HTTPS decryption in fakenet-ng, which is what the sample is trying to connect to the C2 server with.

Looking in the results of the fakenet-ng logs, I don’t see any actual

HTTP/HTTPS

traffic.

And after looking into the logs of particular connections (that I pulled from Procmon), I still don’t see anything interesting that is readable:

As for the Powershell logs, I don’t see anything interesting that is

logged around the time that powershell was created in procmon.